When asked, “What does African-American art mean to you?” I reflected upon “art as a creative expression of one’s imagination that emerges as visual oral and aural reality.” Historically, African-American art emanated from our Mother Continent, portraying a dichotomy of oppression and pain juxtaposed with a desire for power and freedom. It is a haunting echo of a rhythmic and sensual drum beat and as aesthetically unique as the subtleties of nature itself in color and contour.

“Black art” embraces all facets of soul and spirit across all cultural and generational boundaries as it depicts and explores how our people have been perceived by self and others. It is manifested through a multitude of forms, embracing fine art, music, architecture, dance, textiles, photography, graphics, poetry, creative oral expression, functional and decorative design and the literary. Today, as in yesteryear, we continue to express our inner challenges, outer jubilations and visions for our future, as we leave a legacy of a controversial mosaic for the world to digest, critique and enjoy.

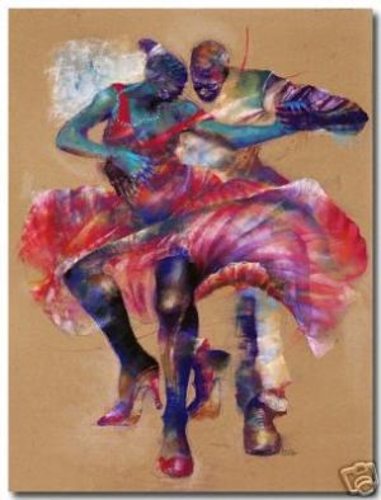

When I was asked, ”What do you like about African-American art?” a myriad of images cavorted before me as they cascaded from my memory like beads from a broken Maasai neckpiece. When confronted with the need to give decisive answers and make selective choices about something or someone, I always sing softly to myself a revered hymn, “Open My Eyes That I May See.” I spontaneously engage in this exercise in order to comprehend any submerged intent beyond my initial impression, or to derive a personal connection beyond the obvious. In answer to October Gallery’s question, several artists’ conceptualizations emerge as my favorites: White Chocolate by Lady Bird Strickland, which parallels my historical biography of an ancestral Southern plantation and slave ownership, with mixed heritage. Another is Ascension by Larry “Poncho” Brown, which exalts my exuberant faith. Among the many others, however, it is Paul Goodnight who “sang my song” as he captured my essence in his rendition of The Landlord.

Initially, as I often gazed upon this ecstatic, hip-swinging, feet stomping, rambunctious dance, I could “hear” the tempestuous rhapsody and “feel” the rhythmic vibrations as I pondered why I was enchanted with it. Why had Goodnight imbued it with that provocative title? Does their synergy suggest that the landlord and his tenant are having an affair? They are certainly extolling their mutual joy!

Hmmmm!!

Later, on one quiet, pensive evening, I instinctively knew the source of my pictorial adoration.

It was that presently, as the shades of night begin to descend upon my twilight years, this rendering by Paul Goodnight reminds me that I too am having a glorious affair with my landlord…the Man upstairs…our Heavenly Father, who holds my infinite mortgage. As His tenant, I find that Goodnight’s “visual song” resonates my joyful expression of gratitude to Him for his magnanimous gift of longevity.

Gratitude and enchantment are universal and expressed so artistically and eloquently in the many melodic, lyrical, and creative languages within our Mother Continent. A sampling is reflected in Yoruba when the Nigerians say, “Mo was layo fun ayee mi” (I am joyful for my life). The Dinkas of the Sudan are rhythmical in their refrain, “Yic ya piox yice rec” (In me life is good.) And in Liberia, “nyelleh eh deh coo poh yah be kwa deh yenneh poh ageh coo y mammah say e mahn minni mma!” ( We share our workmanship (art) with the world to thank You for Your blessings). In America, “Hallelujah!” says it all.

I am proud to acclaim African-American art as a legacy of birth from the womb of our African Homeland, and am intrigued by the belief, proposed in some arenas of idealism, that our first Black artist is Our Creator of Life.

Erlene Bass Nelson, Ed.D.

Educator

Philadelphia, PA

Posted By: October Gallery

Posted By: October Gallery

Sunday, April 11th 2010 at 7:48PM

You can also

click

here to view all posts by this author...